Someday we will be shocked no one could tell.

Stream-of-Consciousness / Final Critique, 2011

2025 update: thus far, the best thing for my autism has been being a solo video game developer.

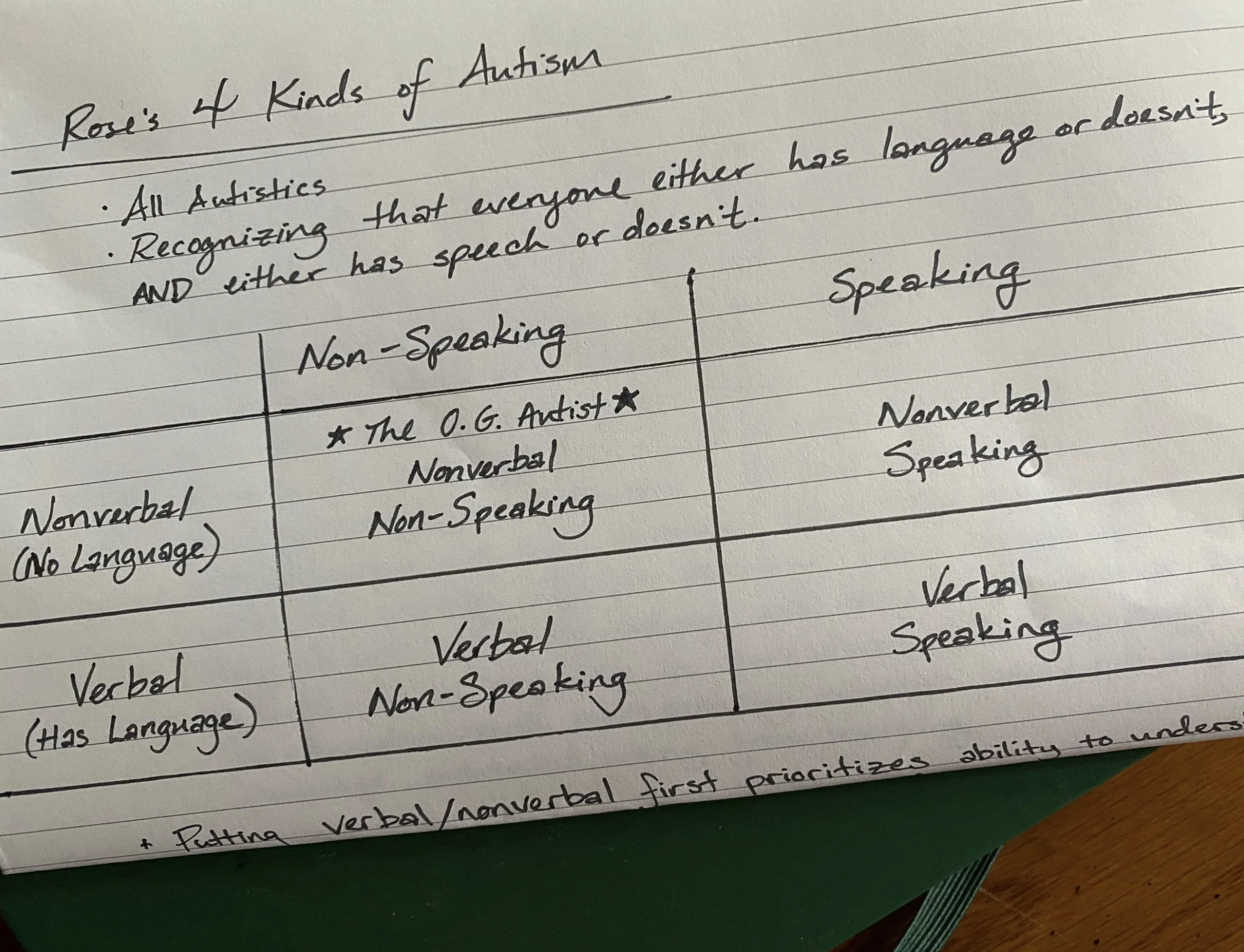

I have observed constant fighting over which one term should be used for autistic people (sometimes shortened to “autistics”), what we should be called by others, others believing it’s subjective and therefore polite to ask for preferred terms, accusations of insensitivity for not using “person first” language—person with autism has been rejected by many who joke that we are not “with” our autism—while all kinds of autism research tries to keep up with this terminology, I’m not finding recognition that regarding autism and communication, there are two components of verbiage, which I’m generally seeing conflated into the latter: having language and speaking it.

Whether someone is speaking or non-speaking, those of us who don’t have language (nonverbal) are high support needs by definition. Currently, within the autism community and those who are learning about autism, when someone finds out a person is autistic, the first question is whether they are speaking or non-speaking. This question does not answer whether they have language, which is to say they are able to communicate—non-speaking autistic children and adults have always been able to gain access to language through letterboards and other forms of writing, and over the past few decades, AAC (Augmented and Alternative Communication) devices have been developed for non-speaking people to have a digital voice. When a person does not have language, and those with language attempt to train them to speak, they may acquire the ability to speak but not an understanding of how to use language for themselves; this is a critical factor when it comes to having autonomy in the world. There is a threshold, a point at which one crosses over into language, and then they can learn from there (see “Words” from RadioLab).

Understanding autism may depend upon making this distinction, which has nothing to do with behavior, capacity for self-perception, or support needs: we either have language or we don’t and we are speaking or not. The diversity of needs and abilities is covered by the framework I’ve outlined above because the terms do not strictly mean “always speaking” or “always has language”, they are baselines—many autistic people experience selective mutism, for example. When the answer to the first question most people ask about an autistic person is that they are non-speaking, it is generally meant that they do not speak because they cannot speak, not that they choose not to speak. Some people gain the ability to speak with training. For non-speakers who will never be able to use their vocal cords to speak, it is important for all of us to accept this is true.

How can someone speak if they are nonverbal (do not have language)? To be verbal is to have language: one can have language and be unable to speak it, as speaking is integral but not necessary to learning any language. It is more difficult for us to understand how someone could speak without having language—when they do, the person is perceived as simply mimicking speech without intention or understanding. That’s almost it: if we don’t have language, we can’t understand what's being said beyond simple yes/no commands, visual demonstration or pointing. But the assumption has been that these are people who can’t learn, leaving many non-speakers who have language but no way to express it experiencing life locked into their minds. Conversely, to be speaking yet nonverbal subjects one to being approached and taught as if they have language for being “able to speak” when what they have is a most basic form of echolalia: repeating a word or phrase because it’s soothing to say, and for no other reason.

Echolalia is a complex condition that can be understood when it is correctly identified and unpacked but when it is instead taken as regular speech, it is misinterpreted as those who hear it project meaning onto the speaker according to allistic (n0n-autistic) logic. Nonverbal emotional reactions to thoughts about the past, understanding something at a long delay as in days or weeks, often means reacting to these thoughts by laughing, making a whiny noise, crying to oneself, etc. Witnesses to these events apply the autistic person’s behavior to their understanding of their shared present environment, rather than recognizing its awkwardness as possibly an “echo” from the autistic person’s memory. When the autistic person stands out in an environment such as a dinner table, the collective perception is that they are laughing, screaming, or crying in reaction to that which everyone else is paying attention, and there is nothing the autistic person can do to correct the misunderstanding. In those social environments such as family gatherings, college parties, work or community events—anywhere non-autistic people (allistics) are there in part because they are aware they are being perceived—they have a tendency to decide that any sound, any expressed emotion, however soft, is personally directed at them for the sake of communicating judgment (a soft sound can be interpreted as passive aggressive but so can silence and a blank facial expression); that autistic people are simultaneously notorious for not paying attention to other people makes me laugh every time.

Echolalia is experienced by all kinds of autistic people, and when it happens to me, sometimes I am able to stifle or remove myself and explain, but I can still forget I need to add that these reactions are not directed at others in the space, were not necessarily triggered by what was going on, that I wasn’t laughing at what I heard someone say, or crying in response to someone walking into the room. I also forget that in social engagements, what people think happened matters more than what actually happened, and while in life you don’t usually have a stage upon which to give your explanation, most people don’t want to hear it anyway.

Many of us want to believe that if those in the environment knew about autism, they would filter their perception, applying knowledge of something like echolalia because they learned the term. Sadly, informing people someone is autistic, or educating people who don’t have an autistic person in their personal lives, is typically met by the unrelenting assumption that this means the autistic person and/or their advocates want social passes for bad behavior, an acceptance of an offensive person rather than accepting that their first interpretation of that person’s behavior was incorrect.

Known for hitting ourselves—while difficulty with theory of mind is part of autism diagnosis—I do not think autistic people generally know that being perceived harming oneself is emotionally harmful to witnesses; try telling autistic people this, our brains might listen to this reason. From what I understand, when an autistic person hits their body repeatedly, it is an action that relieves muscular tension. Autistic people tend to carry extreme muscular tension without being aware of it (interoception), and that can be caused and/or exacerbated by shallow breathing, sitting in one position for hours, standing on the edges of our feet, and other default sensory overload coping postures that harm us without harming others. Relieving muscular tension in the jaw, neck, forearms, legs, is something autistic people may need to be told to do—if we aren’t told this will be an issue, and if we don’t have people in our lives who understand this need, we may end up banging our arms on body parts like the neck and shoulders, banging forearms on railings and in doorways, as we struggle to regulate our nervous system, as we struggle to breathe, much less relax. That this can come out during times of frustration makes it look like just an anger problem, like threatening violence toward others present, and that is not what it is—I’m not going to claim it can’t be that because that is abuse, and it can happen on top of anything, but that’s what is happening when autistic people are actually being abusive—autism is not inherently abusive, and an autistic person lashing out physically at others is a dire situation that was reached, not our starting point. I don’t suggest trying to talk to autistic people about how much it hurts you to see them hit themselves, telling them how much you love them, and patting yourself on the back for trying, again—that is the wrong approach, not unlike teaching a speaking nonverbal person and counting their echos as progress. Instead I recommend telling the autistic person the legal decisions we have made about what constitutes abuse; if you have been abusive to the autistic person in your life, this will be revealing for you, and you should not take the autistic person’s recognition of your abuse according to the law as extreme, overly strict, black and white thinking; that dismissal according to autistic disability is part of your abuse. Just apologize.

Misunderstandings: Oppositional Defiance

First of all, if you don’t have oppositional defiance, and someone asks if you do, the most accurate response is oppositional, so we need to accept that many autistic people do not have oppositional defiance. Being gullible and wanting the world to continue to make sense according to existing rules (even an incorrect rule in your head like you’re not autistic when you are) can make autistic people susceptible to following incorrect paths of logic when trying to understand why we are the way we are, and while some of us do suffer from oppositional defiance in addition to autism, it is a separate condition not integral to autism. The perception of autistic adults as childish can affect judgment, and people tend to project meaning where they wouldn’t without the negative assumptions attached to the unpredictability and potential threat of an adult-sized child.

Despite the definition of hypervigilance being sensitivity and generally heightened awareness of one’s environment making existence physically overstimulating to the brain, we see “hypervigilance” listed in autism traits and tend to conflate it with oppositional defiance; it’s not the same thing, though it is worth noting this problem and that as it happens, witnesses expect oppositional defiance from the sufferer, making the condition worse. For example, for autistic people to learn we should breathe deeply and as calmly as possible while experiencing hypervigilance because breathing helps relax the muscles, regulate blood circulation, and get oxygen to the brain, anyone trying to help must learn that resistance to this command of “calm down” (often delivered with a defensive body posture aimed at us) is coming with the belief we are being told to calm down and breathe in order to dismiss what we need, or are trying and failing to communicate specifically because we are too visibly upset or otherwise underperforming socially (salt in the perpetually open wound).

If my neck is so tight, I can’t speak, and all I can do to relieve the tension is bang my forearm on it, you’ll need to know that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing—it is safe to say autistic people have generally been unaware that while doing this to help ourselves breathe, you the viewer could be deciding we are hitting ourselves to send a message to you, to get what we want in a most selfish way, to get a treat, like a child, or an animal. That our hitting our bodies seems like abuse toward other people is a way they justify holding onto their incorrect, contrived perception when it comes to this specifically. Believe me when I say I understand autistic people have the capacity to be abusive—it is in the majority of our stories. Hear me out when I say some of us are just trying to breathe, to relieve the tension in our physical bodies, whether or not we are aware that’s what we’re doing by banging an arm on a doorway. Regarding autism only, I’m confident this is the case when it comes to this kind of behavior, and it has nothing to do with making you feel something while watching us harm ourselves (again, that autistic people struggle with theory of mind should make this a non-issue but here we are). The harm in this case is being done by the social environment that is literally suffocating to the shallow-breathing autistic person experiencing hypervigilance. Non-autistic people can do better by understanding this is what is happening.

A non-autistic person overwhelmed by their environment remembers they can step outside, go to the bathroom, unbutton the top button of their shirt—the autistic person’s brain is not performing this executive thinking, and they will benefit from being reminded. I have a theory, if anybody cares, that even autistic people who do not like to be touched can be calmed by having our backs rubbed in a particular way, not too much pressure, over any clothing or jacket, just an even amount of pressure in a circle over the back between the shoulder blades. I’ve asked my acupuncturist and my chiropractor to do this at the end of our sessions and it really helps. Several of my autistic friends have experienced instant relief from my back rubs as well. Sadly, one cannot do it to soothe oneself.

^ points if you noticed I misspelled stupid